Music

Lyrics

Said the shepherd to his wife

The crop of hay is cut and dried

I'll bale it up and bring it in,

Before the coming storm begins

Go, she said, and beat the storm

And then there is another chore

Today the baby will be born,

You'll take me to the hospital

Said the shepherd, if it's true,

'Twere better if I stayed with you

I'd rather let the harvest go,

And hasten to the hospital

Nay, she told him, I'll be fine,

We both have laboring to do

You do yours and I'll do mine,

And the babe will wait 'til the work is *through

• • • • •

The shepherd rode the yellow rows,

The clouds above and the field below

Until the bales had all been tied,

Then home returned to find his wife

The sweat was wet upon her brow,

Her breath it cameth labouredly

And then the rain was coming down,

Upon the field of yellow hay

Said the shepherd, it's no use,

The rain will surely win the race

'Twere better if we let it fall,

And hurry to the hospital

Go, she said, and work with haste,

And bring the bales into the barn

Else the crop will go to waste,

And the babe will wait 'til the work is done

• • • • •

The shepherd drove into the storm,

And to and from the yellow barn

'Til half the bales were safely in,

Then went to find his wife again

How many times her name he called,

And no replying would she make

Her breath it cameth not at all,

She would not rise from where she lay

• • • • •

The storm was o'er within the hour,

The shepherd saw the sun come out

The shepherd's wife saw ne'er again,

He buried her and the babe within

He turned the seed into the ground,

He brought the flock to feed thereon

He held the cleaver and the plow,

And the shepherd's work was never done

Analysis

I consider Shepherd to be at the heart of Young Man in America. Along with Wilderland, Dyin' Day, and He Did, Shepherd creates the uniquely Americana mythos of the album – the formative parables of the American life that Mitchell is creating, evoking, interrogating, and critiquing through the album.

As track 9 of the 11-track album, Shepherd's emotional weight makes Young Man in America into an end-accented album (to borrow Witold Lutosławski's idea of the end-accented form). Mitchell saves the "culmination" and the "emotional payoff" of the trajectory of the album for this almost-ending moment approximately 75% of the way through the album. This is necessary for Young Man in America to hit us with the force that Mitchell is mustering – she needs to have the time in the preceding 8 tracks to weave the web of interconnected meaning and signification, activating concepts from patriarchy, nationalism, rugged individualism, religious fundamentalism, and other areas.

While Ships is the longest track of the album at 6:25, Young Man in America and Shepherd are tied for second place, indicating the way in which these tracks breathe at the beginning and end of Mitchell's journey.

This breathing is particularly important as we analyze the musical features of the track, which opens with a 30-second instrumental prelude and pauses throughout to impose unexpected moments of reflective space.

This occurs not only at a formal macro-level (we hear 4 stanzas, an instrumental interlude, 4 more stanzas, interlude, 2 stanzas, interlude, and 2 stanzas), but also within the regular hypermeter of the musical surface.1

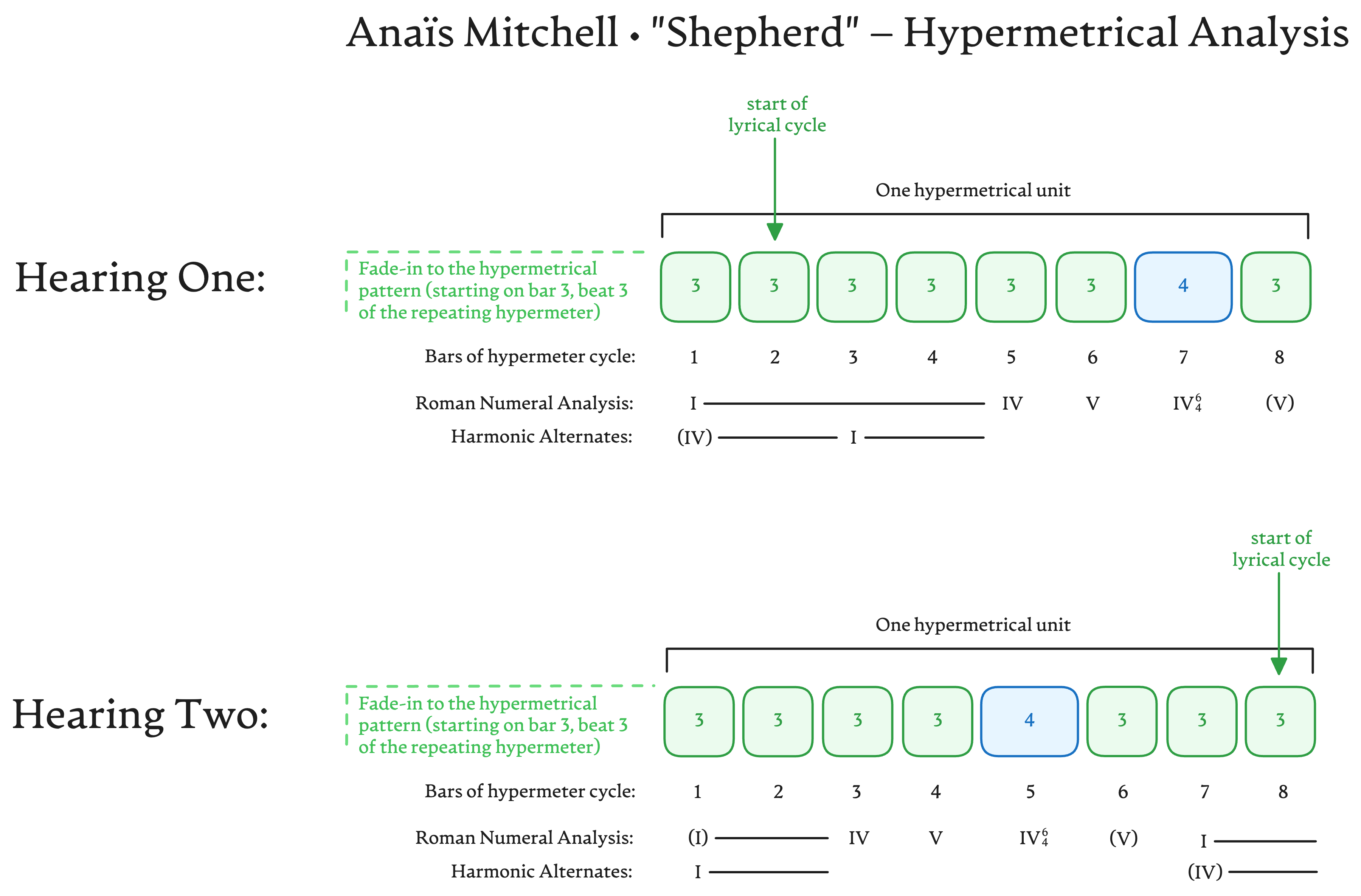

As listeners, we are entrained into a regular 3/4 time signature, but encounter one "swing-bar" per 8-bar cycle – a bar of 4/4 which disrupts the otherwise regular flow of our hypermetrical expectations while retaining the underlying quarter-note pulse. This irregularity of the underlying heartbeat of the track comes to mirror the ragged breathing of the shepherd's wife – "her breath it cameth labouredly" – with each swing-bar imitating a "hitch" in her breathing as the air suddenly catches and is interrupted. (Alternately, one may hear each of the 7 "short" bars as a shallow breathing pattern with the 8th "long" bar as a brief moment of a deep-breathing reprieve).

The "start" or onset of this hypermetrical pattern sometimes feels as though it shifts throughout Shepherd – most often, we hear the swing bar as coming in the 7th unit of the pattern, but occasionally this regularity is rotated such that the swing bar falls in the 5th unit of the pattern. The determination about which "version" of the pattern we are hearing is made by harmonic or dynamic emphasis. For example, an unexpected "extra" 4/4 swing bar occurs on the lyric "through" at the end of stanza 4 (two bars after the previous 4/4 swing bar), and this has the effect of immediately destabilizing the phrase-level downbeat of the hypermeter. Are we listeners supposed to hear that the overall pattern has immediately "rotated" backwards by two bars due to this new appearance of a swing bar (hearing two), or are we to continue counting the regular hypermeter in spite of the intrusion of an unexpected swing bar (hearing one)?

An initial listen is likely to temporarily jostle the listener into hearing two before the "correction" to hearing one comes at the next regular downbeat.

It's worth noting that the importance of this swing bar is consistently reinforced through an extension, pause, or melisma of the lyrics (indicated in bold in the lyrics above) and also through the fact that the usually contrapuntal or hocketing guitars (panned left and right for the listener) regularly coincide rhythmically during each of these swing bars.

Embedded in these rhythmical structures is a regular attack of a light percussive sound on each offbeat (snare drum played with light brushes?) that evokes a gently ticking clock that constantly marks time in the background. (In this story – the seconds counting down before both the harvest and the wife & child expire).

The musical timbres of the track are subdued, primarily acoustic, and reflective with electronic elements or woodwinds occasionally adding a mystique of the transcendent to the every-day simplicity of the core timbres.

The lyrics occupy a heightened register reminiscent of the King James translation or of a stylized Aesop fable:

"Said the shepherd to his wife …"

and

"Her breath it cameth labouredly…"

and

"'Twere better if we let it fall…"

The diction is intended to place the story, the characters, and the situation of narrative into a near-mythological sphere. We are told of the the shepherd and his wife – not of two characters with names, histories, qualities, personalities, etc. These characters stand in for the ubiquitous dream of the (white, heteronormative) nuclear couple. They are hardworking farmers and they are expecting a child. As we have heard in the album already, they are the symbols of America – its plight, its promises, its struggles, and its destructive forces. They are the father and the mother of Wilderland, the father of Dyin' Day, and the father of He Did.

The shepherd and his wife (note – not the Woman and her husband) are the stand-in for so many intersecting axes of American experience – precarity, gender dynamics, economic hardship, community isolation, the tyranny of market forces, natural disaster, western individualism, etc.

The story begins and ends with labor – the hay is waiting to be bailed and brought into the barn and must be done so before the crop is ruined by the coming storm. Nature is the immediate exterior force threatening the lives and livelihoods of the shepherd and his wife, and time becomes the immediate and relentless impetus pressing the narrative forward.

The wife's first dialogue in reply to the shepherd reads at first as encouragement – "go and beat the storm", but her response turns to the other pressing need of the day – "and then there is another chore…". Mitchell intentionally situates the life of the wife and unborn child in the context as labor – it is but another chore of the day, and the wife insists again to the shepherd in the following stanzas, "We both have laboring to do / You do yours and I'll do mine, / And the babe will wait 'til the work is through."

At one level, the wife's lines are a wonderfully playful pun on the dual meanings of labor in the context of harvesting and of childbirth, but in the broader context of the song and of the album, Mitchell is activating a broader critique of labor under the American values of independence, hard work, and the understanding that it is labor that confers purpose upon the worker's life. It is labor that provides a broader socio-cultural meaning for the worker. It is labor which acts as a purifying moral agent – from as early as the Jamestown settlers arriving in this country, the work is the thing that sanctifies our souls and justifies our participation in the community – "He who does not work, neither shall he eat" was the declaration borne out of the Protestant Work Ethic transplanted to Jamestown in 1608.

But there are yet other items to notice in the dialogue. The shepherd's wife announces, "Today the baby will be born, / You'll take me to the hospital". We might expect any number of emotions to bleed through such lyrics – excitement at the arrival of a precious new life, dread for the coming pain, difficulty, and danger of giving birth, anything. But the wife frames this as the other "chore" of the day in a move that underplays her emotional and physical needs (not to mention safety) for the sake of her husband.

We can read some items into these first few stanzas – no mention is made of other children, of other neighbors, of any community or family whatsoever, or of any purpose at the heart of the harvest. The timing itself is also unexplained – yes both the baby and the harvest are quickening and ripening "in the fullness of time," but surely some preparation could have been made for the possibility that both would need tending to at the same moment. Where are the family members, the neighbors, the friends, the ministers – those who should be present when help is needed?

It may be that the shepherd and his wife are truly alone – strangers in a strange land with no connections, no relationships, and no money to their name. I think it more likely that Mitchell wants us to understand the shepherd and his wife as victims of the precarity of all-or-nothing rural subsistence, victims of the isolation of rugged individualism, and victims of the indifference with which both the elements and the state treat human life in America.

The third stanza brings us into the potentialities of this story – the shepherd's hopeful (doubting?) "if it's true" tumbles into his anticipation to care for his wife and get to the hospital. Crucially, he tells her, "I'd rather let the harvest go", which we might read as an earnest statement of his priorities (it may be harder to feed the sheep, but we can make do), or perhaps a means of shirking responsibility for making an impossible choice (we can go, but this will be the cost).

The wife promises, "the babe will wait 'til the work is through" – a claim that she can't know to be true – and we are left to wonder once again if she believes what she is saying or if she is trying to assuage her husband, herself, or both.

At this point in the narrative we can see the cascading pressures and responsibilities that scarcity has imposed on our protagonists. The life of the child depends upon the choice of the mother and the father, both of whom are caught in the negotiations of parenthood, partnership, and labor. In turn, the shepherd and his wife are reliant upon the land they tend, the elements, and almost certainly the economic demands of their creditors, bank, or local government.

On an ideological level, they are responsible to the project of Westward Expansion – the ongoing settler colonialism which was touted as the "God-given right" of white families to take possession of the land, to determine their destiny, and to bring the twin religions of the Messiah and the marketplace to the wilderness. This leaves them forced into an artificial and unsustainable independence – far from the hospital in the city, far from family, far from neighbors, far from a religious community. They become an isolated island of precarity – in service to the bank, the Bible, and the birthright of the nation – but without anyone or anything to call upon for support.

It is telling – at this point – to analyze another latent metaphor in Mitchell's narrative. It is striking that this American pastoral scene so explicitly involves a shepherd and not a farmer. Of course the shepherd is tending both a flock as well as the crops to feed them, but he is identified as a shepherd first of all – it is the third word of the song and the only title by which he is called. Tellingly, we find no mention of sheep until the final stanza. Because of the specificity of diction throughout the song, I choose to read this as a double-entendre meant to evoke the metaphorical life of a minister and his wife.

The shepherd and his wife are therefore under the even greater ideological demands of giving life for the sheep (if they are to mis-apply the scriptural understanding as so many actual people in ministry tend to do). In this context, the pressures placed upon the couple are heightened by the largely-unseen flock – the many mouths that demand feeding and which have no knowledge of, interest in, or care for the shepherd, wife, and unborn child.

This reading, of course, falls in neatly with the reading of Dyin' Day earlier in the album, which has already activated the story of the binding of Isaac, the salvific narrative of penal substitutionary atonement, and the principle that the "blood of the innocent" must be shed to "please the God of Abraham." Speaking from first-hand experience as the son of a minister, the mis-interpretation of these Biblical stories and their mis-application to the lives of pastors and their families is frighteningly common. It is an everyday expectation that pastors and their families will go above and beyond what can be reasonably expected of a salaried employee to care for the lives of sometimes hundreds of people. Importantly, most pastors' spouses (particularly women) are never compensated for the work that they are expected to do. And in the case of ministry children, there is (of course) no freedom for them to "opt-out" of being in a ministry family. They have no power in the final calculation to obtain the fair compensation and professional boundaries of time and energy that their ministry parent(s) deserve(s). Those in ministry are expected to make a second crucifixion for their sheep, with all of their dependents paying the price. Tellingly, the shepherd must both tend the flock and support his "ministry" growing hay – pace, Paul with all your tent-making.

The tragedy of Shepherd lies in the way that this nexus of pressures from religious doctrine, labor, market forces, the poison ideology of rugged individualism, and the willing self-crucifixion of those in ministry flows quietly as an undercurrent beneath the narrative.

The shepherd has the choice to stay with his wife, ignoring her assurances and deciding to go to the hospital anyway. Tellingly, he ties the bales and then returns home – worry, indecision, or just the division of his attention prevents him from committing to either finishing his work or taking his wife to receive care.

As he returns to his wife, the image of the waters of creation comes to the fore – sweat forms on her brow as she feels the first birth-pangs, at some point we may imagine that her water breaks, and we are told that the rain begins to fall. "Her breath it cameth labouredly" – a ruach of potentiality that may not be far from "let there be light." It is a scene that should be rich with both the promises of new life and of the life of the religious community – the waters of baptism, the blessed rains which fall on the just and the unjust. But it is also filled with the curses of Genesis 3 – here it is not only the wife who must experience pain in childbirth but it is also the wife who now labors by the sweat of her brow. All of the precarity which flows down from the state, from the market, from the (lack of) community, from the spirit of the West, from the Protestant work ethic, and from the demands of the sheep are consolidated in her (and thus in her unborn child).

The shepherd and his wife have one last moment of negotiation together. He speaks with clarity now – "The rain will surely win the race / 'Twere better if we let it fall, / And hurry to the hospital". The wife again insists that the unborn child can and will wait, though now she explicitly gives the reasoning for her insistence. It is not merely that there are two forms of labor that the shepherd and wife must manage (public and domestic spheres of responsibility) – now she says, "else the crop will go to waste".

A break for an instrumental interlude at this portion of the text draws this moment into a sharp relief, as though Mitchell wants us to feel the weight of an extended silence between shepherd and wife here. Perhaps he is lingering in the doorframe, looking at his wife to assess the desperation of her condition with one eye out the door to brood on the rain clouds. And perhaps he pushes down the fear that he is taking a final look at her and their unborn child.

In the end, the shepherd can only manage half of the work that needs doing. He returns to search for his wife – "Her breath it cameth not at all". The threatening rains mock the pair – one dead, one grieving – leaving within the hour.

In the last five lines, Mitchell wants us to feel the full force of the final consequences – the tragic decisions that this couple have made in the face of all the pressures of precarity heaped upon their heads.

The wife and child are buried, and we are told rather ambiguously that "He turned the seed into the ground, / He brought the flock to feed thereon" – the quick succession of these three statements leads us to believe that the flock now feeds from the grasses planted over the grave of the shepherd's wife and unborn child. It is a quietly desperate image – a grief so aching for the shepherd that in continuing to try and be near to both family and work, there is no rest or privacy or priority for the family even in death. Their burial plot must be made to be productive for the flock. There is no inch of the earth which can be let to lie fallow. For the shepherd perhaps their is consolation in being close to his loved ones in some strange manner, but for the dignity of the wife and child as human beings, all of this is subsumed under the bitter solace of the shepherd and the needs of the flock.

Two final lines call back to Dyin' Day and drive home the inane and needless futility of this tragic way of life – like Abraham, the shepherd wields the sacrificial cleaver in his hand. Like all ministers throughout time, "the shepherd's work was never done," and the shepherd was incapable of leaving it be.

Last modified: 08-31-2025

-

Just like "meter" (or "time signature") is the term we use to describe how strong and weak beats group together to form a larger, repeating pattern in each bar of music, "hypermeter" is the term we use to describe the way that measures themselves group together to form strong and weak pulses in time. ↩